For several long months in the 1990s, Ronald Sherman travelled all over southern California catching flies. As a qualified doctor pursuing an infectious diseases fellowship, Sherman was curious about a potential new – and also very old – way to clean wounds. At medical school, he’d written a paper on the history of maggot therapy, tracing how the creepy crawlies helped heal soldiers in the Napoleonic wars, the American civil war and the First World War. Now Sherman wanted to test maggots in a modern setting. The problem? No one farmed and sold the species of flies that the doctor needed – so he went out and caught them himself.

Once the specimens were collected and “as soon as everyone stopped laughing”, Sherman got to work. After treating his first patients with maggots, he was impressed by the results, but nonetheless he struggled to get his initial research papers published. A rejection letter from one journal read: “Publishing the manuscript might be interpreted as an endorsement for a therapy that is ancient.” Yet today, Sherman says, “that same journal probably has two or three articles about maggot therapy every year!”

It is believed that ancient aboriginal tribes used maggots to treat the wounded and some academics argue that the practice “dates back to the beginnings of civilisation”. Hundreds of years later, these superbugs are now used to fight superbugs. In an age of growing antibiotic resistance, maggots are an alternative to modern medicine, as they help to fight infection by consuming dead tissue and bacteria. Between 2007 and 2019, the number of NHS patients treated with maggots increased by 47{fe463f59fb70c5c01486843be1d66c13e664ed3ae921464fa884afebcc0ffe6c}.

Meanwhile, there is a farm in Wales that supplies 60,000 medicinal leeches to the NHS and other healthcare providers every year. While most of us imagine that bloodsucking fell out of favour after the Middle Ages, leeches have been consistent healthcare assistants for centuries. The parasites release chemicals that thin the blood and inhibit clotting, meaning they can prevent tissue death by improving blood circulation in areas where it has slowed. In this way, they can save limbs from amputation after nasty accidents.

Honey, which the ancient Egyptians used to treat wounds thousands of years ago, is in use, too. While medical grade honey dressings are sometimes used by the NHS, in September 2022, scientists at the University of Manchester argued that the sticky stuff should be considered as an alternative to antimicrobial drugs. “One thing is certain,” said postgraduate researcher Joel Yupanqui Mieles, “rising global antibiotic resistance is stimulating the development of novel therapies as alternatives to combat infections – and honey, we think, has a role to play in that.”

Meet the new medicine – same as the old medicine. In an age where robots can perform hip replacements and livers can be repaired with lab-grown cells, why are ancient practices coming back into favour? Who are the doctors, farmers, professors and patients who have kept our ancestors’ practices alive? And are there more retired remedies hiding in the archives, ready to be revived?

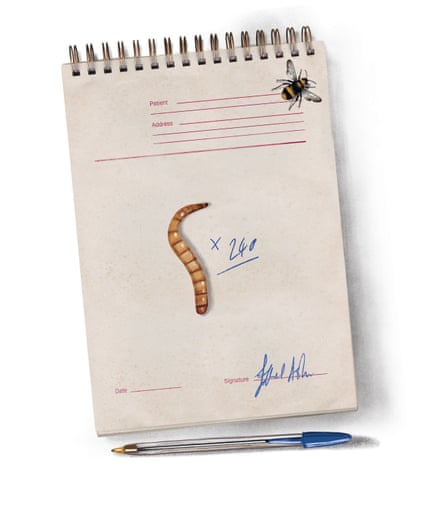

“There is a taboo that gets in the way of people using the technique,” says Sherman of maggot therapy. “But for many practitioners, once they try their first case – even if it’s a last resort – they see what it can do.” Studies have found that maggots reduce a wound’s surface area and promote healing faster than conventional dressings. Following Sherman’s work and the concurrent work of British doctor Steve Thomas, the NHS accepted the use of maggot therapy in 2004. In 2005, a private company spun out from the Welsh NHS Trust where Thomas worked – ZooBiotic, now BioMonde – a sterile maggot-production facility in Wales that is currently home to 24,000 flies.

Vicky Phillips, a clinical support manager at BioMonde, educates clinicians about the benefits of maggot therapy. “The larvae will only eat dead tissue,” she explains. BioMonde’s maggots are shipped out in aseptic polyester nets known as BioBags, each one made to order with a patient in mind, the larvae bagged in the morning and shipped in the afternoon in insulated boxes.

“I think there’s only one postcode we haven’t shipped to in the whole of the UK,” she says. BioMonde is the sole provider of medical maggots to the NHS, and an average of 9,000 BioBags are sent out to UK healthcare providers every year. The bags come in five different sizes and each is used for a four-day treatment cycle, after which the maggots are disposed of as clinical waste. “I always tell patients and clinicians that these are the cleanest little maggots that they’re ever going to meet,” Phillips says – the flies’ eggs are disinfected before they hatch. While a Nursing Times study published in October 2022 found that a “yuck factor” was preventing nurses from using maggot therapy, Phillips says acceptance has increased over the four years she’s been at BioMonde. “Generally, clinicians are more and more keen to avoid using antibiotic therapy,” she comments.

Patients, somewhat surprisingly, are also keen. Rosalyn Thomas is an acute foot podiatrist for Swansea Bay University Health Board who has been using maggots on her patients for 26 years. Thomas specialises in diabetic foot care and has found maggot therapy to be “the quickest way to clean up a wound” – it is an alternative to invasive and costly surgery and it is less disruptive for patients, who can often go home after having a bag applied. For these reasons, Thomas has found that patients are happy to give maggots a go. “Over the 26 years, I’ve only had one patient who took about three weeks to reluctantly agree, but she did agree in the end,” she says. “I can’t recall anybody point blank refusing to have the treatment.”

So what exactly does maggot therapy feel like? Susan Barnard, a type 1 diabetic who had maggots applied to a foot wound in 2016, says “to begin with, it doesn’t feel like anything, really.” The 48-year-old from Holywood, Northern Ireland, compares BioBags to teabags and says the maggots inside look like grains of rice. But as the maggots fed on Barnard’s wound, they grew, and then she started to feel “a crawling, like how your skin crawls but without the shivers”. Still, she didn’t feel squeamish about the treatment – she was simply amazed, and “actually felt really guilty” that the maggots had to die after they’d eaten her flesh.

Carl Peters-Bond is glad I’ve called. It gives him a break from sorting through leeches at his farm – the UK’s only leech farm, which provides the NHS with predatory worms. “I was just about to pick some leeches. Most of them are kept cold and at the moment they’re about 9C. Cold, wet hands at 9C is quite… yes,” Peters-Bond says. “In a really busy year, we can sort through more than 1m leeches, which is very heavy on the fingers.”

BioPharm Leeches is a 211-year-old company that Peters-Bond has worked at for 31 years. In the 1990s, the farm produced “a few hundred” leeches a year, “and then it steadily increased for the next 20 years up until about 2018”. Leech therapy – also known as hirudotherapy – helps improve circulation and speed healing, making it particularly useful after reconstructive or plastic surgery.

Peters-Bond breeds his leeches in tanks – newborns are fed on sheep’s blood five days after they hatch and continue to feed intermittently for the better part of a year until they’ve grown, at which point they’re starved from between six months to two years to minimise the presence of bacteria in their gut. BioPharm’s leeches are shipped in small plastic containers “very similar to what you have coleslaw in” and hospitals keep them in fridges for up to three months.

Leech therapy can last anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour, after which the gorged bloodsuckers end their lives in BioPharm’s leech disposal kits (called Nos da – “goodnight” in Welsh). “They pour on a liquid, which gets the leeches quietly drunk and then there’s a stronger solution to finish them off,” Peters-Bond says.

In medieval times, leeches were used for bloodletting because it was believed to balance the body’s four humours – obviously, this is not what hirudotherapy is about today. Still, the presence of (wanted) maggots and leeches in modern hospitals might make many wonder whether there is more still that we could learn from our ancestors. Christina Lee is one of the founding members of the AncientBiotics team at the University of Nottingham. Formed in 2013, this research group is made up of medievalists and scientists who investigate the efficacy of long-forgotten remedies.

“What is actually quite novel is to have this collaboration between scientists and people in the arts,” says Lee, an English professor who researches Anglo-Saxon notions of health and disease. Lee stresses that the AncientBiotics team’s work is not about alternative medicine or cooking up lotions and potions to try yourself at home. Instead, it’s about looking for scientifically sound remedies that could inspire modern drug discovery.

“I was very, very critical,” Lee says of her initial reaction to testing out ancient remedies. “I thought, this is not something that works.” Yet when she and her colleagues tested out a 1,000-year-old Anglo-Saxon treatment for eye infections, they were amazed by the results.

After mixing allium (garlic, onion and leek) together with wine and bile from a cow’s stomach (oxgall), the team tested the mixtures on artificial wounds and later sent the recipe to America to be tested on mice. In 2015, they reported that the remedy – translated by Lee from a 10th-century medical textbook, Bald’s Leechbook – killed 90{fe463f59fb70c5c01486843be1d66c13e664ed3ae921464fa884afebcc0ffe6c} of MRSA bacteria in wounds. The AncientBiotics team believe it is not one ingredient that made the salve so potent, but the combination that had an effect.

“It felt incredible,” Lee says of the discovery – but questions remained. “If it worked, why was it given up? Is it that at some point it became redundant, something better came out? Or is it that this was something only known to a few people?” Lee believes we can learn a lot from our ancestors because “wounds must have been ubiquitous” in agrarian societies. “If you cut yourself with a scythe, it was highly likely that you’d get an infection.”

Following their discovery, the AncientBiotics team received funding from Diabetes UK to test their salve on human cells – yet despite its early success, the group hasn’t always found it easy to secure funding. “There is a certain resistance,” Lee says. “We’re still working on it.” Lee’s work is often far from easy – a medieval strawberry differs from a modern strawberry, for example, and the team try to use organic ingredients cultivated in the same soil conditions they might have been centuries ago.

I ask her what she hopes the ultimate outcome of the team’s work will be. “There is a major, major problem with antibiotic resistance,” Lee says. “My hope is that help can be found.”

If help is found, will anyone listen? Steve Thomas, the now 74-year-old doctor who helped bring maggots into the NHS (and was subsequently awarded an OBE) says, “If Jenner tried to get approval for his work on cowpox and smallpox today, it would never get off the ground!” Though Thomas declined to be interviewed because of his age and the fact he has “left maggots behind”, he shared some thoughts via email.

“Any product designed for medicinal use has to go through a rigorous safety-testing programme and regulatory affairs process before it is approved for human use. If successful, this leads to clinical studies. These are incredibly time-consuming and very expensive and with a few exceptions almost always funded by the industry,” he writes. “No company will invest the sort of money to carry out this work on a product that they cannot patent.”

Thomas is currently studying the use of allicin, a molecule found in garlic, to treat lung infections. He is also researching whether there is an antiviral agent in slug slime after he used the sticky stuff to treat his own warts.

In August 2022, the University of Cambridge’s Libraries launched a two-year “Curious Cures” project to digitise 8,000 medieval medical recipes. The project will allow greater access to our ancestors – ultimately, it will be far less time-consuming for academics to search through manuscripts. It is possible that people like AncientBiotics’ Lee might find something within these writings – something significant.

In years to come, remedies from years gone by may become commonplace. Three decades after Sherman had to catch his own flies, maggot therapy is a regular and respected treatment. It remains to be seen what else might come back into vogue, but, for now, Sherman is just pleased that the medical world listened – even if the taboo isn’t completely broken. “I’m glad that the world is now more open to the idea,” he says, “and mostly I feel glad that I’ve been able to directly or indirectly help a lot of people save their limbs.”