In September 2018, the pain in my ribs and back erupted almost overnight. I ignored it at first, sure that I had done too many abdominal exercises at the gym. When the pain persisted for a few weeks, I went to my doctor. She was a bit concerned, but all my blood and urine tests came back normal.

Two months later, the pain intensified and started waking me at night. I made an appointment with a physical therapist. Within 10 minutes of examining me, a shadow came over the therapist’s face. “I don’t want to alarm you, but this pain is not muscular-skeletal,” she told me. “You need to get a CT scan. Today.”

Later that day—the Wednesday before Thanksgiving—my husband Greg and I sat in our local hospital’s emergency department, waiting for scan results. When the ED doctor returned to my room, her tone was serious. “We found something we totally didn’t expect,” she said. “There is a suspicious mass on your pancreas that looks like cancer. I’m so, so sorry.”

A chill shivered down my entire body. From my experience as a health writer, I already knew that pancreatic was one of the deadliest types of cancer I could have.

Somehow, my brain immediately switched to medical reporter mode and I asked questions. I must have been in shock, but I managed to take extra-meticulous notes, almost as if my neatly written words let me take some control over the information I had just heard. When I look back at those pages now, I barely recognize my own handwriting.

What is pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is the third deadliest cancer in the United States. Around three in four patients die within a year of being diagnosed. And what makes this cancer especially sneaky is that its early symptoms are so vague: Abdominal or back aches. A little stomach discomfort. Some bloating. Stuff you might feel if you ate too much at dinner. Nothing you would take seriously at all.

In addition, most common blood tests don’t detect pancreatic cancer. By the time the cancer is discovered, the tumor has usually grown quite large. It may also have spread outside the pancreas, to the liver, lungs or, more rarely, abdominal fluid that may have collected due to the cancer. This cancer is quick moving and deadly.

In my case, the pancreatic tumor was about the size of a golf ball, but had not yet spread. However, it was wrapped so tightly around several aortic and liver-related blood vessels that they were almost completely blocked. Removing the tumor surgically was next to impossible. My only option was aggressive chemotherapy. It might extend my life, but it was not expected to cure me.

But I understood none of this on the night before Thanksgiving. All I knew was that my life was forever changed. I felt that our daughters, ages 17 and 21, were still too young to lose their mother without it leaving a permanent scar. My husband and I had been married 29 years and were as close as we’d ever been. Now our shared future was dissolving in front of my eyes.

At 3 a.m. on Thanksgiving morning, I got up, unable to sleep. I padded quietly downstairs to our dining room and set the table for dinner with our extended family. I folded napkins and laid out silverware and plates. I set out bowls for mashed potatoes, stuffing, gravy and vegetables and tucked tiny yellow sticky notes into each dish so I’d remember which was which.

Then I gave up and dissolved onto the cool, hardwood floor. I lay down flat, my face touching the wood, and began to pray. “Please, God, give me time. Give me time to be with my daughters and Greg. Please give me more time.”

This is what it feels like to be diagnosed with cancer

Until you actually experience it, you cannot possibly know how you’ll handle the news that you might be dying. My first reaction was, quite strangely, relief. I can let up now. I don’t have to work so hard at this thing called life, because it’s almost over, I thought to myself.

I had not realized until my diagnosis how utterly exhausted I was. I’d spent the past decade dealing with the stress of caring for both of my aging parents (now deceased), my husband’s recent job loss, maintaining my own freelance writing business and worrying over various issues related to my daughters’ health and education. Looking back, I believe that this cycle of chronic stress could have encouraged the cancer to take hold. I had none of the common risk factors that could explain this deadly diagnosis.

But within days of getting this frightening news, a spark of new energy ignited inside me. I wasn’t ready to die. I was determined to use every research skill I had learned throughout my writing career to prolong my own life.

That was more than three years ago. The doctors initially told me I had about 18 months to live. Since my diagnosis, I’ve learned more than I ever expected about cancer treatment and how critical it is for us patients—not just our doctors—to take active roles in our own healing journeys.

Coping with my pancreatic cancer treatment

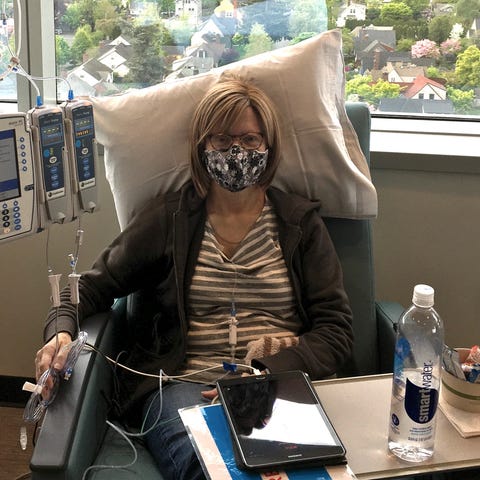

The most effective chemotherapy regimen for pancreatic cancer is a rigorous one called FOLFIRINOX that lasts for three days at a stretch. It required me to sit in a cancer center infusion room for eight hours, then go home with a chemo pump attached to a vein in my chest for 46 more hours. I repeated that cycle every two weeks.

I experienced all the classic chemo symptoms: fatigue, unrelenting nausea and diarrhea, loss of appetite and a metallic taste in my mouth that made even plain water taste horrible. One of the chemo drugs caused my hands and feet to go numb, a condition called neuropathy. I couldn’t close clasps on necklaces or type accurately on my laptop. The numbness in my feet made me constantly trip when I walked.

When I wasn’t leaning over the toilet retching, I was researching pancreatic cancer to see if I could improve my odds of living. My research led me to make a bunch of lifestyle changes: I adopted a ketogenic diet, which some health researchers believe may help stop certain types of cancer from growing. I completely stopped eating sugar, too, to give my body every health benefit I could.

I read research by Valter Longo, Ph.D., of the University of Southern California, who discovered that fasting might make chemotherapy more effective and help reduce chemo-related side effects such as nausea and mouth sores. For 48 hours before and 24 hours during each of my biweekly chemo sessions, I stopped eating and drank only water and herbal tea. I lost 30 pounds I didn’t need, then learned how to stabilize my weight during my non-fasting days.

Maintaining hope also became a key part of my treatment. I asked my oncologist to stop talking to me about survival statistics or time frames unless I specifically asked. I also began searching online for pancreatic cancer survivors. I found Marla through a work colleague and Jane through a hospital website. I emailed and talked to both women by phone about what they were doing to stay alive. I also joined a number of patient-led cancer Facebook groups.

In addition, I meditated, prayed, underwent Reiki healing sessions, and used guided visualization to imagine my tumor being dissolved by a healing white light. Friends and family rallied around me, and set up a GoFundMe account to help Greg and me with our ongoing expenses.

After several months, new scans showed that the chemo and my extra efforts were working! Not only had the cancer stopped growing, the tumor was actually shrinking. My pain also disappeared. It looked like tumor-removal surgery might be a possibility.

The life-saving surgery just outside my reach

I set my sights on consulting one of the country’s top pancreatic surgeons at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. My health insurer initially refused to allow me to go outside my home state of Oregon for care. It took three months of vigorous appeals, and the help of a friend who worked in the insurance field, but my insurance company eventually relented. I visited the Mayo Clinic surgeon in May 2019 and he gave me a tentative OK for lifesaving pancreatic surgery.

I went home to Oregon with a few more health milestones to complete, and we tentatively scheduled the pancreatic surgery for that September. Greg and I felt like we had just won the health care lottery!

Unfortunately, our celebration was short-lived. Just a month later, I ended up in the hospital. It appeared that I had a life-threatening reaction to one of my chemotherapy medications and it almost stopped my heart. Two days later, coincidentally, I had emergency gallbladder surgery. During that operation, my surgeon noticed several tiny, cancerous lesions on my liver. With that, I was considered a stage 4, or “terminal” cancer patient. Because of those tiny liver tumors, the Mayo Clinic cancelled my pancreatic surgery. My family and I were heartbroken.

For several weeks after getting this news, I could barely function. It seemed that my only hope for a cure had been ripped out from under me. Then, by pure coincidence, I ran across an intriguing book: How to Starve Cancer…and Then Kill it With Ferroptosis by Jane McLelland. This book opened the door to an entirely new world of unconventional cancer treatment and to patients who were working with open-minded doctors to direct their own care.

The beginnings of my unconventional approach

How to Starve Cancer isn’t a book about food or lack thereof. It’s actually part memoir, part geeky medical research by a London-based woman who survived stage 4 cervical cancer. McLelland’s self-studied treatment includes using a cocktail of fairly well known, nontoxic, generic drugs and natural supplements to block cancer from growing.

The FDA-approved drugs McLelland describes were originally developed for use with other medical conditions, including diabetes, high cholesterol, and ulcers. In recent years, though, researchers have found that these drugs may have anti-cancer properties. Using these drugs to treat cancer instead of their originally targeted health conditions is considered “off label” use.

As I delved into this new world, I learned that many other medical professionals and researchers were also enthusiastic about the possibility of using so-called off-label or repurposed drugs to fight cancer. Patients and medical professionals have developed entire Facebook groups devoted to helping each other understand how to use and access these prescriptions.

I felt a wave of newfound hope: Could patients like me actually beat back a deadly disease like pancreatic cancer with a handful of inexpensive, often-forgotten prescription drugs? I wasn’t sure, but I knew one thing for certain: I had nothing to lose by trying. There was no cure waiting in the wings for me.

I printed off medical research papers about a few of the drugs and their potentially cancer-fighting properties and excitedly took them to my next chemotherapy appointment. When I showed them to my oncologist, Rui Li., M.D., Ph.D., her reaction was swift and firm: She absolutely refused to prescribe any of the drugs and scared me into thinking I might seriously harm myself by trying them.

Now, I’m not normally a rule breaker. I was a teacher-pleasing student in school. I wait for green lights at crosswalks. And I have no delusions that I, a layperson, understand cancer better than someone who has graduated from medical school. But at this point, I had a terminal cancer diagnosis. My husband Greg and I both agreed that we didn’t want to look back later with regret and say, “If only we had tried those off-label drugs.” I consulted two other doctors, who both agreed that the off-label drugs I was considered were, indeed, safe. That was all the reassurance I needed.

My journey with off-label drugs for pancreatic cancer

I felt really uncomfortable doing so, but I decided not to tell my oncologist what I had decided. Instead, I consulted Dave Allderdice, N.D., FABNO, a naturopath in my hometown who specializes in working with cancer patients.

With Allderdice’s help and Greg’s full support, I slowly added off-label drugs to my many daily supplements. The naturopath prescribed one drug at a time. I’d take it for two weeks, then he’d review my blood work and check on side effects. As each drug proved safe, we added another, and then another. I bought an acrylic jewelry sorter to store the dozens of pills I took three times a day.

Some of my fellow patients accessed these same off-label drugs a different way: through a group of experts that have organized themselves through a group called the Care Oncology Clinic (COC). Based in both the United Kingdom and the United States, these doctors’ primary goal is meeting virtually with cancer patients who want to try this experimental approach.

The only reasons I didn’t use the COC were 1) I had already found a local provider who could help me, and 2) cost. The prescription drugs cost the same no matter who prescribes them, but COC doctors charge consulting fees. Still, if this had been my only way to access the drugs, I absolutely would have consulted a COC practitioner.

Every month when I picked up the off-label drugs at our local pharmacy, I worried that my oncologist, Dr. Li, would somehow get an alert about my new prescriptions. It never happened. And when the medical assistant asked me at my biweekly chemotherapy appointments about any new prescriptions I was taking, I bit my tongue hard (figuratively) and said, “Nope. Nothing new.”

Within a couple of months, my naturopath Allderdice and I could both see that my body was tolerating the prescriptions well. My biweekly blood tests looked good. My tumor continued to shrink. Even my oncologist, Dr. Li, was surprised and pleased about my progress. Every time we got a new, more positive scan, she beamed. “You are doing so well! Your progress is really unusual for pancreatic cancer,” she said.

A handful of fellow pancreatic patients I met on Facebook were also experimenting with off-label prescriptions and supplements. We began sharing notes on side effects, sympathetic doctors and new research. Other patients shared protocols that included dietary changes, cannabidiol, high-dose Vitamin C infusions, and complementary therapies like spending time in hyperbaric oxygen chambers and infrared saunas.

My online pancreatic pals were, and still are, intense researchers, unfailing optimists, and strong advocates for their own health. I felt like I had truly found my tribe. None of us wanted to belong to the cancer club. But if we had to undergo this challenge, we agreed that we were going to do it on our own terms—and share our findings with each other along the way.

Coming clean with my doctor

After about a year of trying the off-label drugs for cancer, I felt the need to be honest with my oncologist. It was a risky move. Several other patients I knew from my Facebook groups had already been “fired” by their oncologists for trying alternative treatments without their doctor’s knowledge.

At a regular chemotherapy appointment, I finally blurted out to Dr. Li: “You know those off-label drugs we talked about, the ones you weren’t excited about?” I asked her. “Well, I’ve actually been taking them for a while. I feel badly not telling you sooner, but this was something I had to do.”

My oncologist’s face immediately registered displeasure. “What? Which drugs? What dosages? Who prescribed these drugs?” she demanded to know. I answered all of her questions. I could see from her queries that her main concern was for my safety. My doctor pulled up my blood-test history on her computer, and I showed her how my key tests had remained steady or even improved while I embarked on the experimental drug regimen.

After our discussion, Dr. Li seemed reassured that I wasn’t a crackpot. However, for the next several weeks, I worried about getting a call or letter that she was refusing to treat me as a patient because I had taken my health into my own hands. That doesn’t mean she fully supports my regimen. “I don’t think the many supplements are the key contributing factors for Teri’s current health,” she says. “It is impossible to identify which supplements really helped.” She adds, “From a scientific view, I do not encourage patients to [take non-prescribed supplements or medicine] without participating in clinical trials.”

But here’s what I kept reminding myself: Stage 4 cancer typically is a death sentence. There is no such thing as stage 5. If a doctor has already told a patient that they cannot cure them, shouldn’t the patient be free to experiment with other, untested treatment options?

Ideally, of course, patients would wait for drug or other treatment regimens to go through exhaustive clinical trials and become part of the standard treatment for their cancer. But pancreatic patients like me—and many others with fast-moving cancers—simply don’t have the luxury of waiting a decade or more for clinical trials to finish and report their results.

Besides that, there is the possibility that unusual approaches like using off-label drugs, cannabis or natural supplements may never get the public attention they might rightfully deserve. Pharmaceutical companies can’t patent or repackage these treatment options and sell them at a nice profit. And if oncologists like mine are suspicious of using anything besides chemotherapy or radiation, how will patients ever learn about other options?

Two weeks after I revealed my drug experiment to my oncologist, we met again. I asked her point-blank: “Are you going to fire me as a patient?” Dr. Li laughed and shook her head. To her great credit, she said she would never get insulted if I got better using drugs someone else had prescribed. “I still don’t completely agree with the idea of these drugs, but I cannot argue with how well you’re doing,” she said. “And I do believe that stage 4 cancer patients should have a right to experiment with their own care.”

Living with cancer—and hope

I’ve now been taking my cocktail of off-label drugs and natural supplements for more than two years. I’ve long since passed my original “expiration date” of 18 months. If I’m fortunate enough to live for two more years—to the five-year survival mark—I’ll be one of only 10 percent of pancreatic cancer patients to survive that long.

I wish I could say that I’m miraculously cured, but I’m not. A tiny remnant of the cancer remains in my pancreas, and rogue tumor cells are likely still circulating throughout my bloodstream. But I have gotten precious extra time on this earth with my friends and family—which is what I prayed for during the predawn hours of Thanksgiving in 2018.

I’ve also learned for myself — and have shared with anyone who will listen — how important it is for patients to research and work alongside their doctors to get the best possible care. I no longer believe that being a polite, rule-following patient is the way to live. That’s especially true if you have a health condition that takes the lives of significantly more people than it spares.

Years ago, I watched a movie called “The Edge.” Anthony Hopkins stars as a wealthy but sheltered businessperson who must make his way out of the Alaskan wilderness (with costar Alec Baldwin) after a freak plane crash.

Hopkins’ character has a single book about survival skills. But that volume encourages the billionaire to repeat a simple phrase whenever he and Baldwin’s character verged on losing hope: “What one [person] can do, another can do.”

I have repeated that same phrase to myself throughout my pancreatic cancer journey. If just one patient can survive this cancer or live a longer-than-expected life—and I know several who have—another person can do the same. Maybe that person can be me.

Signs & Symptoms of Pancreatic Cancer

- Unexplained middle back or stomach pain: A pancreatic tumor can press on the spine, nerves, or nearby organs.

- Stomach bloating: You might be gassier than usual or feel that your stomach is swollen. These symptoms are caused by trouble digesting your food.

- Unintended weight loss: Pancreatic cancer can impact the way your body digests and absorbs nutrients from your food. You may lose weight without trying.

- Yellow skin or eyes: Pancreatic tumors can block the bile that moves from your gallbladder to your small intestine. When this happens, yellowish bilirubin from your bile builds up and is visible in your eyes or skin. You may also have itchy skin, pale-colored stools or dark urine.

- Poop problems: You could suddenly develop ongoing diarrhea, constipation or both.

- Late-onset diabetes: People who become diabetic when they’re 50 or older may be experiencing an early symptom of pancreatic cancer. Someone who already has diabetes and suddenly has trouble controlling their blood sugar should also be evaluated for pancreatic cancer.

Risk Factors for Developing Pancreatic Cancer

- Family history of pancreatic cancer

- History of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- Obesity: Being very overweight increases your risk of this cancer by 20{fe463f59fb70c5c01486843be1d66c13e664ed3ae921464fa884afebcc0ffe6c}

- Smoking: About 25{fe463f59fb70c5c01486843be1d66c13e664ed3ae921464fa884afebcc0ffe6c} of pancreatic cancers are thought to be caused by cigarette smoking.

- Race: Ashkenazi Jews and African Americans have a higher incidence of pancreatic cancer

- Age & gender: Almost all pancreatic cancer patients are over 45, and two-thirds are at least 65. It also impacts men slightly more than women.

Helpful Resources for Pancreatic Cancer Patients

These organizations offer support and information:

- Pancreatic Cancer Action Network: This nonprofit organization offers patient support, helps identify hospitals and specialists that treat pancreatic cancer, connects patients to possible clinical trials and more.

- Project Purple: Pancreatic patients who are facing financial hardships because of their inability to work or medical treatment costs can apply for financial aid once a year.

- Cancer Commons: This network of patients, physicians, and scientists helps patients with all varieties of metastatic cancer (at no charge) explore their best possible treatment plans and clinical trials.

- Foundations: The National Pancreas Foundation, Lustgarten Foundation, and Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreas Cancer Research help fund pancreatic cancer research and offer patient education and support. The Hirshberg Foundation offers patient financial aid.

- Lazarex Cancer Foundation: Lazarex helps advanced cancer patients find FDA-approved clinical trials. It also offers financial support to patients who travel away from home to participate in clinical trials.

These Facebook groups can help you connect with others.

- Pancreatic Cancer Warriors-Patients Only: Support for pancreatic cancer patients

- Stage 4 Pancreatic Cancer Support Group: Support for pancreatic cancer patients and their caregivers

- Jane McLelland Off Label Drugs for Cancer: Support for cancer patients and families who are encouraged to read How to Starve Cancer…and Kill it With Ferroptosis.

- Healing Cancer Study Support Group: Information for cancer patients who are combining traditional and complementary therapies

- Always Hope Cancer Protocol Support Group Support and advice for cancer patients/caregivers who use traditional treatment along with off-label drugs and other therapies; group leader’s late husband had pancreatic cancer.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io